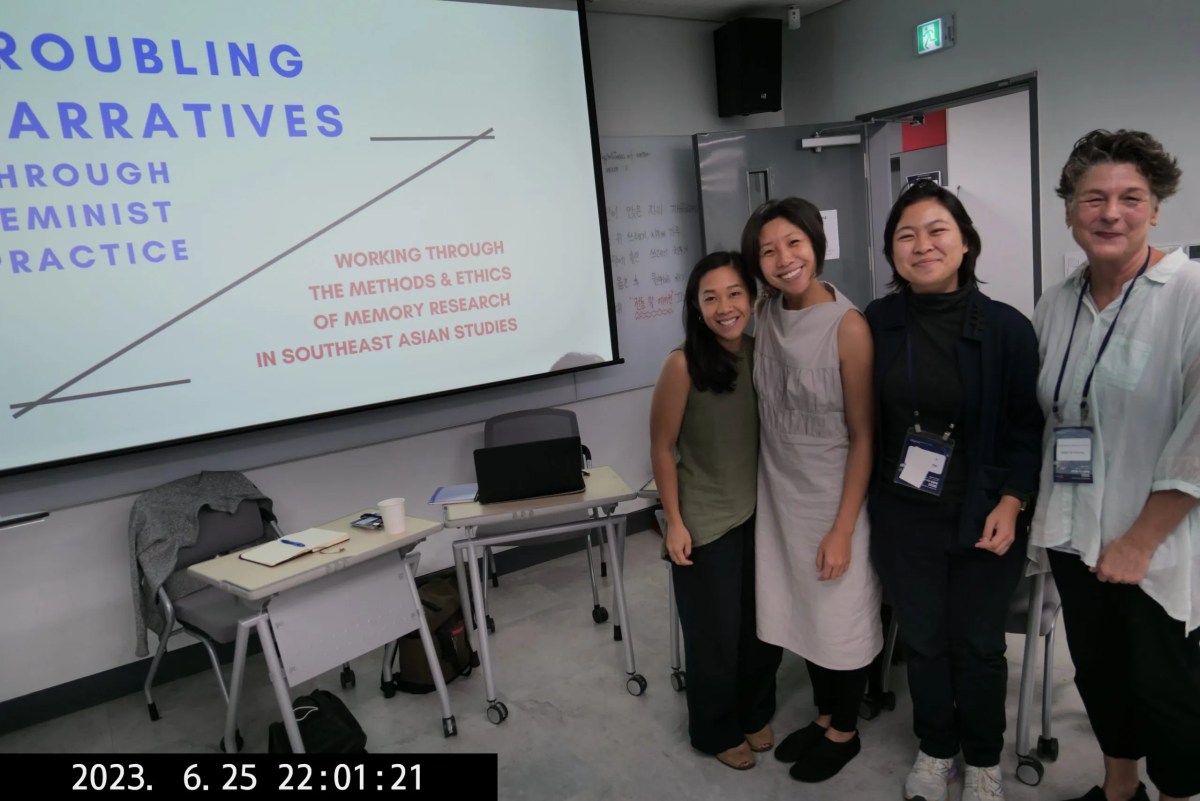

Truly honored to share the excerpts of our publication “Feminist Trouble in Southeast Asia: An Invitation”. It’s been a privilege to work together with fellow troublemakers Tara, Theresa, and Nicole, to redefine academic ‘work’ through relationships and centered on care. What appears like an academic article is more like an imprint of our collective gatherings, dreaming, and cowriting that spanned summer 2022 (submission to AAS in Asia roundtable- part community gathering part academic real talk) to the gathering in the mountains of South Korea in 2023, to finally its written linear format in spring 2025. As I alluded to in my “Collecting Through Absence” piece, this has been a long transitional period of turning towards a different type of scholarly identity and community artist, a feminist troubling of knowledge and narrative, that celebrates relationality, experimentation, and transdisciplinarity–a surrender into the world of “what if” rather than creating from a world of “what is”. This truly is an invitation, please do reach out to join us, dream/make with us. Follow along here: http://mis-reading.com/trouble/

For published article, see

Theresa de Langis, Nicole Yow Wei, Tara Tran, Cindy Anh Nguyen (2025) “Feminist Trouble in Southeast Asia: An Invitation”, Verge: Studies in Global Asias, 11:1, 105-130, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/vrg.2025.a951540

For other pieces in this issue: https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/54274

If you leave a comment with your email/ or email me at cnguyen@seis.ucla.edu, happy to send you the full article without paywall….(shadow library link to file)

Excerpts of Introduction, Conclusion and Citations

Excerpt from my subsection “Care As Knowledge, Care as Labor: Toward Relationally and Making Kin”

I make visible to readers my dreams in all their fragmented mess: to weave together the intellectual, personal, and collective threads in a reflexive troubling tapestry that makes visible care as knowledge and labor. I begin with my historical research on care, abruptly recognize the care work of academic labor, and close with an invitational collective dream of a future informed by feminist and decolonial kinship. I center Haraway’s (2016, 1) reminder that future making is not of imagined safety or of clearing dangers of the past and present but is instead to “make kin in lines of inventive connection as a practice of learning to live and die with each other in a thick present. . . . Staying with the trouble requires learning to be truly present, not as a vanishing pivot between awful or edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.”