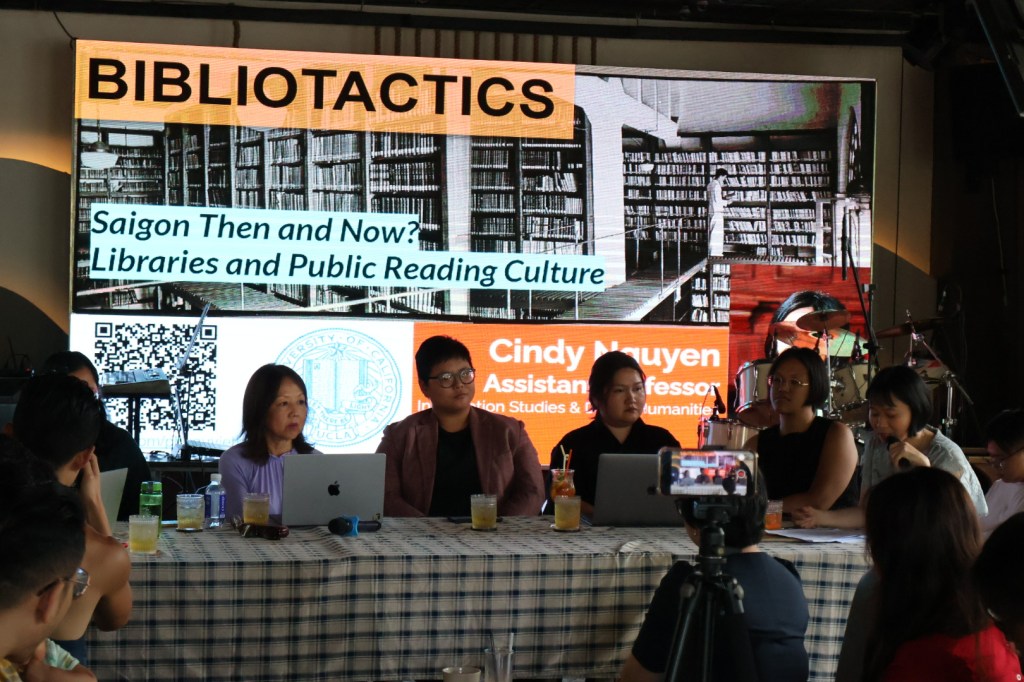

Join us in Saigon for experimental community talks around reading, feminism, and art. It’s an honor and dream to “start” my book tour in Saigon (where the intellectual/personal/political journey began) alongside feminist cothinkers Minh and Yen.

Read more: Saigon Experimental “Book Talks”: Art, Community, Women’s Reading, August 8-9, 2025August 8, 2025: “Library History as Data-Art-Life: Fabulating the Vietnamese Past”

August 9, 2025: “Women’s Reading: Theory and Practice” Roundtable with Cindy Anh Nguyễn, Yến Vũ và Nguyễn Thị Minh

- Nguyen Art Foundation, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Part 1 event details and signup, 10AM

- Part 2 event details and signup, 9AM

- Nguyễn Art Foundation is pleased to present a two-part event (8 & 9 August) that brings together scholars and practitioners exploring the complex entanglements between reading, gender, institutional power, and historical memory in Vietnam and its diasporas. Moving across colonial archives, library histories, and literature, the program rethinks the act of reading – not as passive consumption, but as a site of resistance, imagination, and world-making. Through diverse lenses – feminist critique, critical fabulation, and institutional analysis – these speakers interrogate who gets to read, what is considered public or private, and how gendered dynamics shape literary and cultural encounters. The program highlights how readers, particularly women, have long negotiated visibility, agency, and power through their engagement with texts.

Day 1 – 8 August: Library History as Data-Art-Life: Fabulating the Vietnamese Past with Dr. Cindy Anh Nguyen

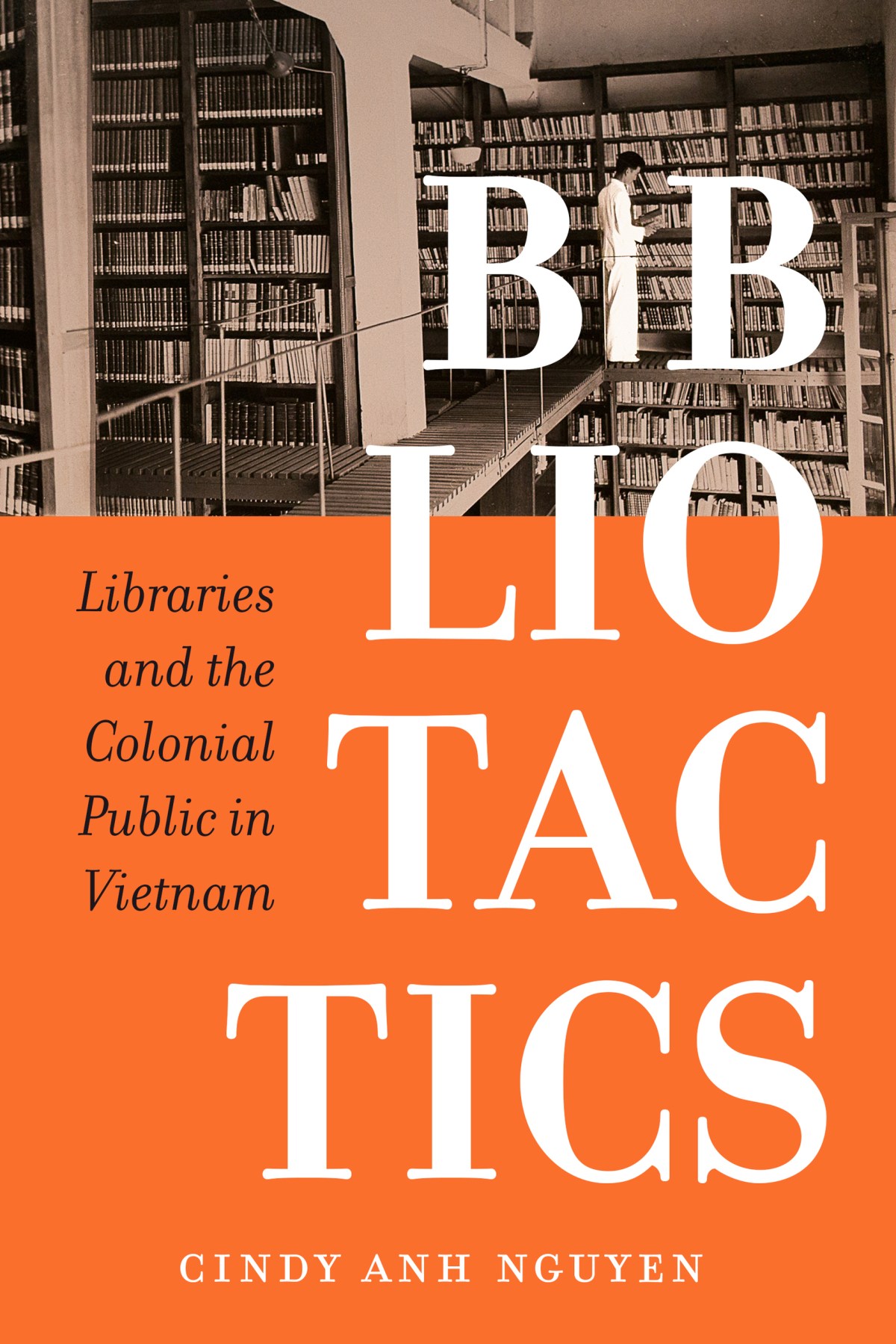

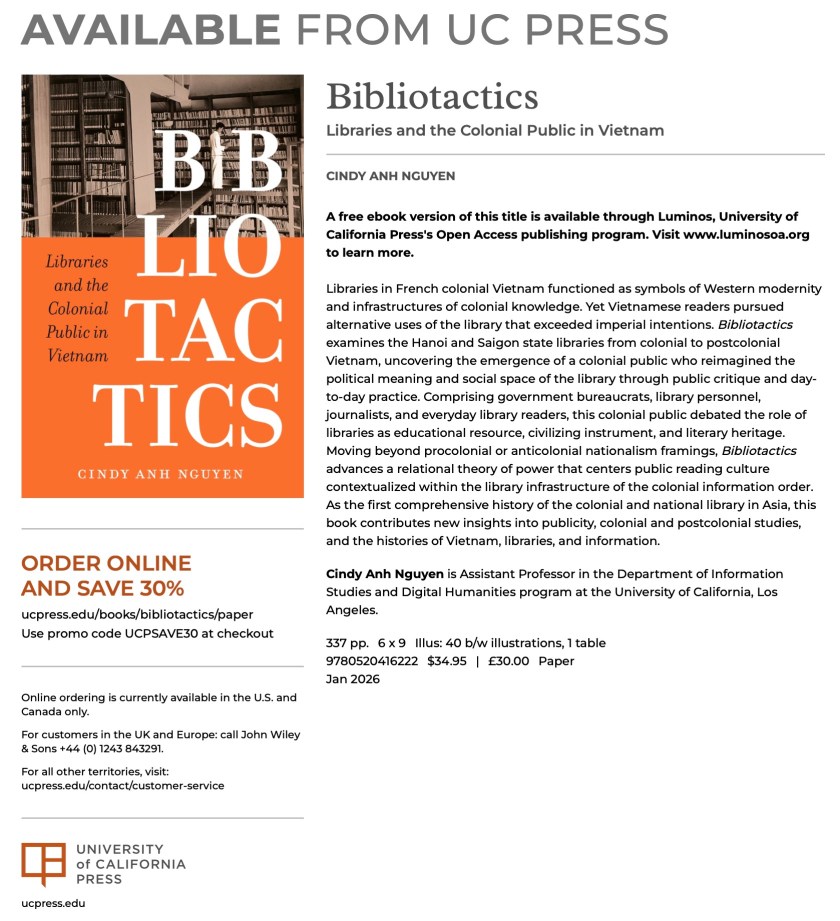

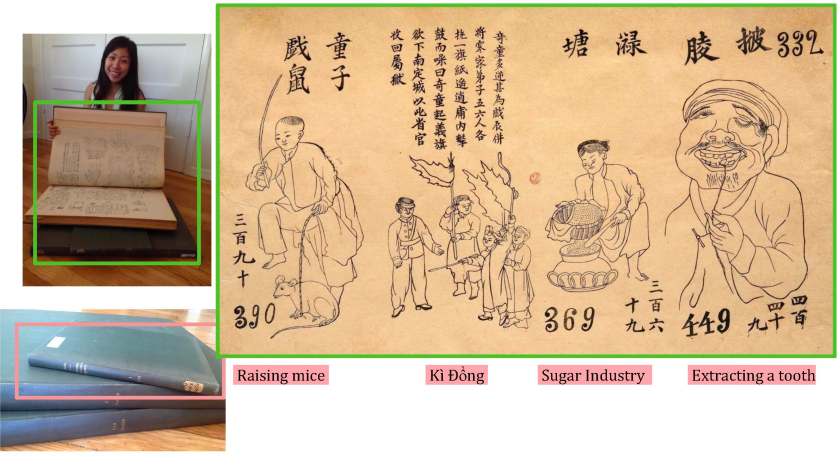

This talk is an invitation into the experimental transdisciplinary approach of Dr Nguyen’s book ‘Bibliotactics: Libraries and the Colonial Public in Vietnam’. Beyond an academic book of Vietnamese history, it is a work of critical fabulation through visual archives, data aesthetics, and experienced architectures. Interweaving method and theory, the author centers historical agency of Vietnamese library readers in colonial institutions, to ultimately trouble questions of power and publicity. This talk moves from static and disciplinary framings of History towards a dynamic crisscrossing of data-art-life that centers absence, imagination, and relationality.

Day 2 – 9 August: Women’s Reading: Theory and Practice with Dr. Cindy Anh Nguyen and Dr. Yen Vu. Moderated by Dr. Nguyen Thi Minh

1/ ‘Women Library Reading Publics and Redefining Publicity in Late Colonial Vietnam’ by Dr. Cindy Anh Nguyen

This presentation explores how late colonial Vietnamese women were central to redefining discursive and functional meanings of publicity. Through tracing the creation of “bình dân thư viện,” these communal and public library initiatives questioned the various political meanings of “bình dân,” the commoner, the people, or accessible to the general public. The author will show how “public” could mean access to a wide range of people, including women, provincial readers, and youth; social welfare for the commoner and disenfranchised; or collective national identity through shared vernacular language and literary heritage. As a public space for cultural exchange, self-erudition, and intellectual discourse in a shared language, Vietnamese public libraries functioned as bottom-up experiments in forming imagined communities of readers and public citizens.

2/ ‘Reading women against the grain: A feminist method among masculine voices’ by Dr. Yen Vu

Can our work still be feminist even if the materials we work on are masculine and exclusionary? How can we read the textual representation of women in a way that is not bound by their definition as characters represented by men? In this talk, Dr. Vu draws from her experience negotiating with gender representation her my own research on francophone writing, dominated by masculine voices. The author will present the case of Tran Van Tung’s francophone novel ‘Bach Yen ou la fille au coeur fidele’ (1946) to exemplify how we can still pose critical questions in line with a feminist epistemology despite the text’s masculinist predispositions. Beyond the gender dynamics of the nationalist cause, the author will also focus on the formal construction of the novel, and how text emerges beyond the intentions of the author.

Bio:

Cindy Anh Nguyen is Assistant Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles with appointments in Information Studies, Digital Humanities Program, and Asian Languages & Culture. Her forthcoming book ‘Bibliotactics: Libraries and the Colonial Public in Vietnam’ (University of California Press, 2026) uncovers how libraries functioned as both instruments of colonial dominance and an experimental space of public critique. Her work has appeared in Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Verge: Studies in Global Asia, Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, the Vietnamese American Refugee Experience Model Curriculum, Wasafiri, Ajar Press, Diacritics, and exhibitions such as ‘Textures of Remembrance: Vietnamese Artists and Writers Reflect on the Vietnamese Diaspora’.

Yen Vu teaches at Fulbright University Vietnam and is a scholar of 20th century Vietnamese literature. Her book project ‘Language as form, the politics and poetics of writing in French in 20th century Vietnam’ explores questions of language, freedom, and intellectual history. She received her PhD from Cornell University and subsequently held appointments in the French Department at Hamilton College and at the Weatherhead East Asia Institute at Columbia University. Her writing has appeared in Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Diaspora, and Environmental Humanities. She also co-hosts a podcast called Nam Phong Dialogues that makes Vietnamese history accessible to the general public.

Nguyen Thi Minh is a tenured lecturer in the Faculty of Linguistics and Literature, Ho Chi Minh City University of Education. She was a visiting scholar at the University of Oregon (2018), a Fulbright scholar at the Asian American Studies Department, UCLA (2022–2023). In addition to translating multiple classical works in philosophy, gender, and cultural studies from English to Vietnamese, Minh works in comparative literature and film adaptation based on gender studies and semiotics, with her latest research publications featured in Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy and Landscape Research in 2025. She is collaborating with the Vietnam Women Publishing House to build the Women’s Book: Gender and Development series to promote Vietnamese gender studies. Minh is the co-founder of The Ladder, an inclusive community learning space, which is making academic knowledge more accessible for everyone, especially the Vietnamese youth.

![Feminist Trouble in Southeast Asia: An Invitation by Theresa de Langis, Nicole Yow Wei, Tara Tran, Cindy Anh Nguyen [New Publication]](https://cindyanguyen.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/p1585441-scaled.jpg-2.webp?w=1200)