In the past, I was frustrated by how slow my work moved. I was impatient that my critical inquiry, confusion, curiosity forced me to constantly revisit sources, translations, historical contexts. Market pressures to publish and produce (a talk, an article, a dissertation, a book, teaching, digital resources) with the promise of professional security perpetuated a structure of external validation of scholarly production.

As I begin this new position at UCLA and transition into my professorial role, I’ve been reflecting on my messy and vibrant intersections of intellectual, personal, and political commitments. My transdisciplinary work in Southeast Asian history, community arts, digital humanities, and collaborative multimodal learning are all unified by an approach of ‘world building.’ I examine worlds past through historical and digital humanistic inquiry. A world building approach recursively makes space for the interwoven work of critique-reimagination of worlds past, present, and future.

At the heart of worldbuilding is an intention to slowness.

I undertake a slow critical approach in world building to take time to wander, wonder, pause, and be deeply embedded in cultural social worlds. I strive towards an ethical responsibility to understand primary sources and data and their affordances of production. I work and walk alongside others in intentional collaborations of knowledge making, honoring overlapping and divergent motivations and interests. We journey in collective writing sprints, organize feminist gatherings of knowledge sharing, workshop rough ideas, and enact tactics of creating near future and distant future realities. Scholarship is a communication ecosystem–through classroom engagements, public talks, side conversations, I revise and revisit my thinking in a persistent commitment to learn and unlearn. All of this work, this quiet labor and recursive journeying is both painfully and pleasurably slow.

Slowness in Teaching (Part 1)

Teaching through pandemic and navigating infrastructures of labor exploitation has left me beyond exhausted. Intentional slowness in teaching is a tactic of self-preservation and invitation towards rest. I counter both internal and external pressures to continually ‘improve’ or ‘innovate’ my teaching with a set of slow tactics:

- Each time I teach a course, I permit myself to only ‘innovate’ (change the structure of the course) in either content or form. That means, I only change the reading/topics or change the structure of assignments/modality.

- I offer assignments that invite in slowness from students rather than structurally add more. For example, rather than another paper or project, I task students with a portfolio assignment that recompiles and reflects on previous work within the classroom.

- Topics are substantively aligned vertically instead of pressures towards horizontal expansion. We take ‘one thing’ and create opportunities to dive deeper, offering space for comparative wonderings but recognize that expertise in all the things is impossible. A final project that hones into the ‘one thing’ allows students to slowly explore.

- At the heart of slowness is creating a class culture and community. As instructor, I dedicate time to learn about students through:

- A simple student questionnaire. Example

- First class session on building a collective class charter. Example

- Revisiting personal goals and experiences in the middle of term through a check in questionnaire. Example

- Creating space to celebrate and commemorate the class journey through a shared activity such as collective ‘yearbook’. See extended discussion of yearbook celebration and other assignments in my Teaching Workshop

Slides from talk: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/17EoKTX5fX7sThm6pR5NmmPYCaTIdVzJm1MNDdZRXspM/edit?usp=sharing

Virtual Reality and Slowness

I joined the Virtual Angkor team late their dissemination stage as a teaching fellow, committed to rethinking how to ‘teaching’ with virtual heritage resources. I designed the following teaching module guided by the question “What does it mean to tour the past?” We carry this out firstly through a slow observation based learning (where often in university environments it’s all about fast, skimming, speed reading, losing the experiential wonderment of it all.) I organized this teaching module be a collective meditation on meaning making, guiding questions, vocalizing understanding, figuring out collectively an unfamiliar historic moment and social world of thirteenth century Angkor.

See complete Virtual Angkor teaching module here: https://cindyanguyen.com/2019/11/25/teaching-virtual-reality-module-analyzing-representations-of-angkor/

Slides on Decolonial Data Pedagogy Lecture with Fulbright-Hays (Middlesex Community College and Lowell Public Schools) Group : https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1zQFZdggH8Tp9ueUeUO0qoH9KRLVHNY6Vfkzqn1vNzjE/edit?usp=sharing

Slow Viewing Workshop Description

In this workshop, Dr. Nguyen invites participants to practice a ‘slow viewing, slow listening, slow thinking,’ process of meaning making in virtual reality that can be taught in classrooms focused on world history, global Asias, and digital media and design. Dr. Nguyen leads an exploration of Virtual Angkor, a virtual reconstruction of the medieval Cambodian capital of Angkor that seeks to explore the diversity and complexity of Southeast Asia in digital heritage studies. Virtual Angkor reappraises the neglected region of Southeast Asia as a dynamic and important center for understanding global processes of premodern urbanisms, climate change, and ‘non-western’ forms of governance and power. This workshop invites participants to enter a VR space to listen, examine, and question. The experience aims to facilitate a ‘critical making’ understanding of the past which undermines the romanticized representations of the exoticized orient or the ruins of Angkor that permeate both the French colonial record and the contemporary tourism industry complex of Cambodia.

Slowness in Research (Part 2)

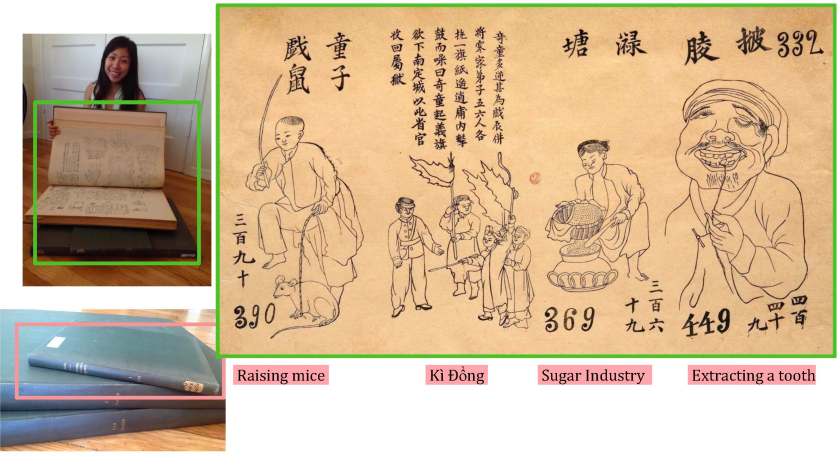

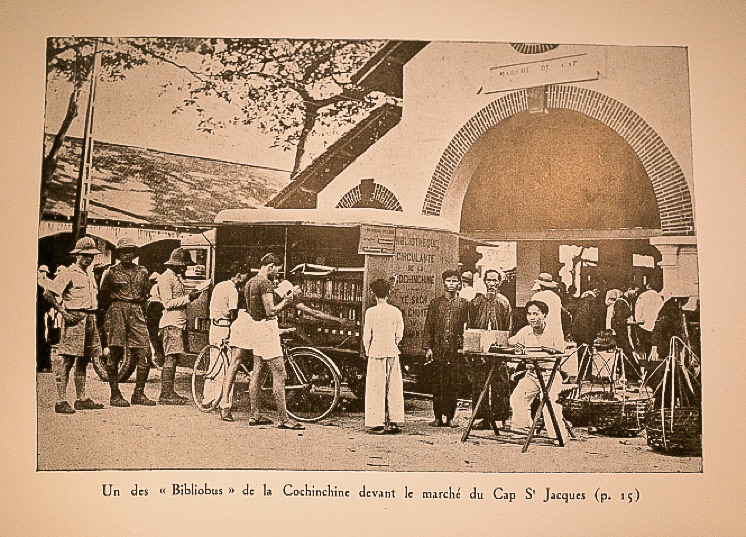

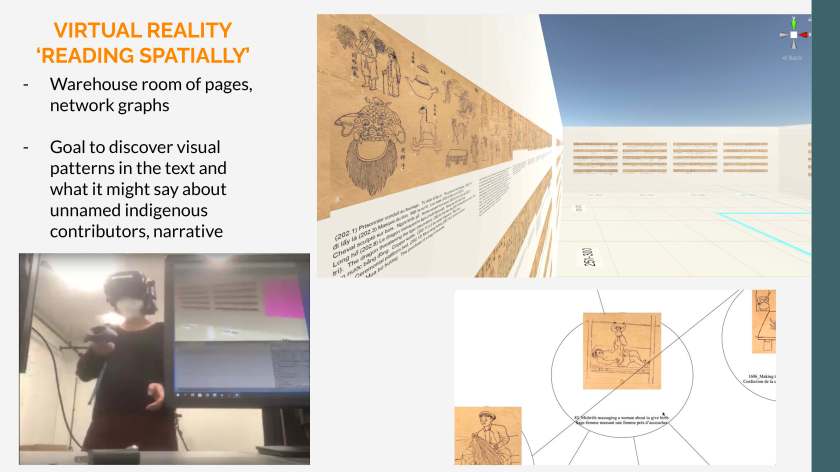

My Decolonial Data Pedagogy Lecture with Fulbright-Hays (Middlesex Community College and Lowell Public Schools) Group (linked to above) has been a culmination of a slow alignment of my pedagogical and research commitments towards imagining a post/anti/decolonial approach to my research on colonial histories and knowledge production. Slowness was at the crux of this material-computational analysis of this peripheral text, Technique du Peuple Annamite, that haunted-mesmerized me since graduate school. After eight years of working on a different project (history of libraries) amongst other life things, I return to this work in full gusto. The slowness of ‘figuring out’ this text through close reading, material analysis, collaborative analysis, and computational modeling has given this work the timespan it needed to breathe and imagine. Digital humanities is not just method, but invited a commitment to decolonial data critique and to platform a decolonial imagining, a building of an alternative world beyond/in contestation with its colonial confines.

Slowness as Method

My regular check in: “Is this new idea/approach/methodology substantive or additive?”

As of late, I’ve been repeatedly told: “You have so much energy!” “You’re so productive!” and I often blink back in cognitive dissonance to the comments because they shroud the quiet, recursive labor of what it means to do teaching and scholarship on the everyday. Folks see the product, not the process.

I’m slowly trudging through a mess and I embrace it. Slowness is a feature not a bug (particularly in virtual reality and computational analysis). Slowness is an invitation to critique and contextualize. Slowness is a pedagogical imperative to permit students to be curious again, to reflect and to celebrate. Slowness is a license to pause, rest, and do nothing.